The reminder of this chapter is an adaptation of "Gnucash and double entry accounting" by Joseph Mack (C) 2001 jmack @ wm7d.net. The original is available online and was released under GPL.

For the purposes of this document, your goal in working is to get as much money as you can for your time. In accounting parlance this is called maximising your return on investment (ROI).

Of course your employer will tell you that your goal is to give the best service possible, and of course you'll agree with him.

In turn your employer when he goes to his customers will tell them that the reason his company exists is to provide the best service possible to them.

Your employer will tell you that he's running his company to get the most money in return for your efforts (his ROI). When he talks to his customers, he tells them that the reason his company exists is to provide the best service possible to them.

It's possible you want to make the world a better place etc, and you use your job for that, but in the end, if you weren't getting money from your job, you wouldn't be able to save the world. So no matter what we tell other people, what we're really interested in is (ta da) the money.

Not only is your money of interest to you, there's other people looking over your shoulder and it's of interest to them too, Here's a partial list of these people.

you

the tax people

bankers, creditors, investors

These people want to know about your money to the penny.

We need to track our money. The two methods used are as follow.

This method is used only for personal accounting. It sees your finances as one (or a small number of) piles of money (accounts). The pile increases (with salary) and decreases (with purchases).

Single entry accounting is simple if your money is in a single (or small number of) accounts (eg a checking account).

In business accounting, money is divided into many piles (accounts) and each account is treated differently.

In your tax form, you'll see that the whole of your expenses for office supplies are taken off the top of your profits, while you can only take off half the expenses for food. To make life easier for yourself, you'll have one account for office supplies and another for food and entertainment. You track the money in each account separately.

You also need to be able to transfer money between accounts. This transfer is called a transaction.

In double entry accounting, there are:

many accounts

movement of money (a transaction) is from one account another (i.e. 2 accounts are required for every transaction). This is where the name "double entry accounting" comes from.

movement of money for different purposes is a matter of making a transaction between the appropriate pairs of accounts

Your personal check account which is a `cash' account, would be named for example `cash:check'. Meaning that you have an account named `cash' and a sub account named `check'.

Accounts for phone and other utilities are `expense' accounts. For example `expense:phone' and `expense:utilities'.

Every time you spend, receive or transfer money is a "transaction". When you write a check to pay your phone bill, that's a transaction. When your paycheck goes into your account - another transaction. When you go to the ATM to get some cash for a night out, that's a transaction. When you buy a burger with that cash ... you guessed it, it's a transaction. | ||

| --From the Linux Journal article by Robert Merkel in the Apr 2001 issue, p122 | ||

In double entry accounting parlace, what happened was:

you need some cash, you go to the ATM and take some money out of your check account (cash:check) and put it in your pocket (cash:petty).

you buy a burger, you credit cash (cash:petty), you put the receipt in a folder and you debit the expense to expenses:food_and_entertainment.

to pay your phone bill you remove some money from your cash:check account and you send it to the phone company (recording it in the expense:phone account).

In all cases money just moves from one place to another. Money does not appear, disappear, get created or destroyed.

Conceptually it's a spreadsheet with:

variable number of tables (accounts).

number of columns in the accounts is the required number for accounting (i.e. all tables have the same number of columns).

different types of accounts (cash, asset, liability, expense...)

columns are pre-labelled according to account type.

an entry in one account is linked a matching entry in another account. If you correct/change an entry in one account, the matching entry and balance will be updated in the other account.

rules are hard wired so that the correct entry will do something sensible to other tables. The wrong entry will produce results that are obviously wrong (even to non-accountants like myself). This won't tell you the correct thing to do (you'll need to understand accounting for this) but at least you'll know there is a problem.

dates automatically generated (or you can enter dates manually).

report generation

Due to the nature of the device FreeCoins is running on, some of these features are not available. For example there is no report generation (FreeCoins relies on external export/conduit programs to gather data and generate meaningful reports) and there are no differently labelled columns in the transaction register. In fact there are no columns at all due to the small size of the screen. However the button labels when entering transactions from different account types change accordingly.

Double entry accounting is a lot more work than is single entry method. It only makes sense when you have a lot of money compared to the cost of keeping track of it (ie you're rich - accountants are cheap it seems).

You do it to catch errors and to accurately track the various streams of money in your business, not only for yourself, but because others want to know your finances and you need to have the information available in a format they understand. The agreed language is double entry accounting.

People had been tracking money (to pay bills, collect taxes) for thousands of years, but it wasn't till the 1400's that the Italians invented double entry accounting. This made banking reliable, enhanced trade and commerce and very quickly Italy became the banking capital and wealthiest country in Europe. It was the 1400's equivalent of the invention of the Internet and the dotcom boom. They had buckets of money to spend. They spent it on paintings of Adam talking to God done on black velvet. Well they would have but velvet hadn't been invented yet. They made do with what they had, which was plaster ceilings. They spent money on painters, sculptors and people like Leonardo da Vinci.

In grade school this period is called the Renaissance, a flowering of art and intellect, that appeared in Italy for no obvious reason and then spread to the rest of Europe.

Quite why all these geniuses suddenly appear without any warning is not explained by your history teachers (who spend their life pondering deep questions like this), but Jared Diamond (Guns, Germs and Steel, Pub: Norton 1997) is happy to tell you. He says that geniuses like Michealangelo and Einstein are rather commonplace. Most of them are oppressed and are living in abject poverty, and are busy surviving if they even do that. Give them a good feed, treat them well, put them in the company of peers and pretty soon they'll be coming up with all sorts of things you hadn't dreamed of.

The Renaissance then was a result of the invention of double entry accounting, not (as we've been told) a flowering of intellect and art that happened for no reason at all.

About 200 years after the invention of double entry accounting, the scientific revolution occured. People realised that you could ask questions of nature (by doing an experiment) and you got answers. Not only that, you got the same answers every time. It was much easier than asking questions of people, who never give the same answer twice. The simple questions were asked first ("do heavier objects fall faster?" - no-one had ever asked nature about this before). This lead to more complicated and more interesting questions. With lots of data rolling in, a mathematical revolution soon followed, one part being calculus.

I found double entry accounting more difficult to learn than calculus. The fact that calculus was invented 200yrs after double entry accounting would indicate that calculus is conceptually more difficult than double entry accounting, but I'll offer the following evidence to support the opposite postulate.

Calculus:

The need for it is obvious. Any 10 year old who tries, even in principle, to calculate the distance travelled by a car by tracking the varying position of a car speedometer needle, is working on deriving integration and numberical methods from first principles.

When presented, calculus is instantly recognisable as the solution to many problems.

People have been able to expand calculus.

The people who invented and expanded science and calculus are known and the circumstances of their work is known.

you can mathematically prove that calculus is correct.

Double Entry accounting:

The need for it is not obvious and so there was never any pressure to invent it.

When presented to you, it doesn't appear to solve any problems. It seems to make them worse. Your first reaction is "you want me to do all that! what for?"

It is revealed wisdom. The names of the inventor(s) of double entry accounting have been kept secret. You can't prove anything about double entry accounting - no-one has proved or derived the self consistent orthogonal set, even 600yrs later. All we know is that it just works. It may as well be magic.

No-one has been able to improve or expand it.

You have to be a lot smarter to invent something for which there is no need, that no-one can understand and for which there is no proof that it's right (other than it works) and for which no modifications have been possible, than to invent something whose need is obvious and which you can check by proof for correctness as you go.

Not only this, the total salaries paid to people who understand accounting is much higher than that paid to the people who understand calculus.

QED.

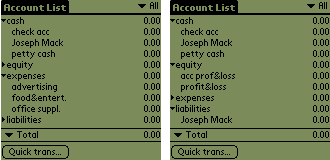

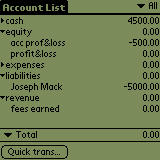

Let's start a one person business, RocketScience LLC. Here's the FreeCoins screen for the moment the business springs into life. The FreeCoins screen comes up blank and I have primed FreeCoins with a minimal set of accounts.

Note that I have grouped accounts of the same type into their own tree. FreeCoins allows you to have accounts in trees like this or to have accounts branching directly from the root. The accounts in the same tree must be of the same type. I found it easier to have accounts of the same type in their own tree. All the expense accounts live in one tree. All the cash accounts live in another. I could have had 2 (or more) cash trees (say) if I wanted. FreeCoins recognises about 5 types of accounts. I'll talk more what a "type" is later.

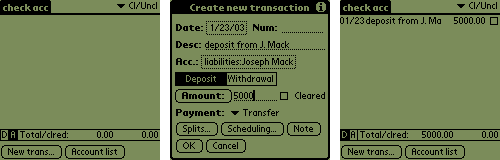

The business needs some capital to buy things, so that you can start work. Since you are the owner, let's assume you're going to put $5000 of your personal money into the business. It's going into the business's check account, which one of the cash accounts (the cash:check account). Here's the cash:check account screen as I'm part way through recording the entry. I record that I deposited check #1234 from my personal check account #9876541 for $5000 into the business's check account.

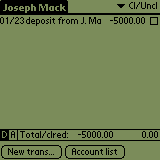

Remember that money only moves around, it didn't just appear. It had to come from somewhere. When I record the deposit, I also record (in the transfer column) where the money came from. Since the owner Joseph Mack put $5000 into the business, the business now owes $5000 to Joseph Mack. This $5000 is called a liability. I record that the money in the business's check account came from the account liabilities."Joseph Mack", capital. The account button in the transfer box allows you to select the "liabilities"Joseph Mack", capital account as the matching account, completing the entry.

Here's the same entry as seen in the matching liabilities:capital account. Note I didn't make the entry seen here. FreeCoins did this automatically, when I selected the liabilities.capital account in the transfer column, in the screen above. Note that the entry is identical (comments, date, amount of money) except that the money is logged as `credit' this time.

If you read in the newspapers that a company is running a lot of red ink, it means they have a too many liabilities and they're in financial trouble. Companies (at least in newspapers) are "in the black" or "in the red". A black balance in an account means you have an asset, a red balance means you have a liability.

In the transaction above, a matching pair of entries creates an account with a black balance (the check account) and another account (the liability account) with an equal red balance. Remember money is not created or destroyed, it's just moved around. We started with 2 accounts at $0 and moved $5000 from one account to another. The target account wound up with (black) $5000 and the source account with (red) $5000. It's the same principle as the creation of matter at the big bang, where in an instant you had the creation of equal amounts of matter and anti-matter. Accountants have been doing the same thing with money for 600 years.

Why is the balance in the liability account red? Isn't a liability already negative and therefore a red liability positive? Accountants presumably could have chosen to do it this way, but instead they chose to make liabilities in all accounts red. That way the accountant doesn't have to flip to somewhere else and find out the account type and risk making a mistake.

While a balance can be black or red, the entries in the debit and credit columns are always black. The numbers in the debit and credit columns are the amount of money that was transferred in the transaction and this is always positive. The effect on the balance can be in the red or black direction depending on whether the entry was a debit or credit.

Liabilities are not neccessarily bad. RocketScience LLC required a liability (to the owner) before it could start business. Banks have liabilities to the people who make deposits. Planned liabilities, which you can cover in the period in which they come due, are a normal part of business. The "red ink" problem are unplanned liabilities or unplanned shortages of cash which don't allow the company to meet its financial obligations as they become due.

There always is a debit and a credit column in an account (seen in the liability account above). The words "debit" and "credit" are an arbitrary pair of words, like positive/negative, male/female, left/right. Because of double entry accounting, every debit is matched by an equal sized credit. Both debits and credits are good.

Normal citizens like you and me may think that credits are good and debits are bad. This is because when you get a copy of your bank statement, and you see a credit amount and you are happy. It turns out, you aren't getting a record of the amount of money you have (although you may think it is). What they send you is a copy of one of their accounts which shows their financial situation i.e. a liability to you. A credit entry then means that that they have to be prepared to pay you money. You are seeing the bank's view of their financial situation, not your view of your situation.

If you were using double entry accounting on your personal finances and had walked into the bank with a pocket full of money, you would have debited the money to your personal petty cash account to match the credit in their account.

A credit in the bank's account which is showing their view of their business with you, just means that they have a liability to you for a certain amount of money, and that you are one of their creditors. The statement doesn't say that you have money. In fact you don't have the money at all, they do. If they go bankrupt, no-one has the money.

A credit doesn't mean that you have money and a debit doesn't either. It's the balance that is important.

Accountants know which is the debit and credit part of a transaction. They spend years learning this stuff. If you ask them, they'll tell you that the credit is the right hand column and the debit is the left hand column. That's the beginning and end of it. However for weenies like you and me there is no hope of remembering whether the action you're taking on an account is debiting or crediting and you'll get it wrong half the time. To help you recognise whether you're crediting or debiting, FreeCoins gives a name to the credit and debit column that is more in line with non-accountant's perception of the transaction. In the check account, when you put money into it, you put the money into the "Receive" (i.e. debit) column and FreeCoins will make the corresponding credit entry for you in the liability account.

All accounts of a particular type (e.g. cash, liability, expense) have the same names in their debit and credit columns (e.g. all cash accounts have "Receive" and "Spend", all expense accounts have "Expense" and "Rebate").

The transactions that most of us think about are between accounts of different types. The account types is the nearest thing to an orthogonal set that I can see in accounting. I don't know whether there is a finite number of account types, or whether the number has changed since double entry accounting was invented.

We're ready to start business.

RocketScience LLC wants to tout its unique skill set to the world to earn some revenue and decides to spend some money on advertising. The tax people require you to track your advertising expenses separately from all other expenses, so you set up an expense.advertising account. RocketScience LLC spends $1000 on a webpage with the latest in Java applet technology. You write a check on the RocketScience LLC bank account and send it to WebSite-R-US.

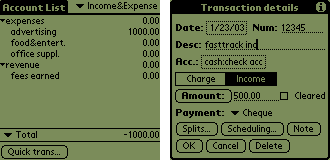

Here's the entry in expenses:advertising. I'm selecting the matching entry from from the cash:check account (you record your check number, #1001, the first written on your bank account). Note that a debit for an expense account in FreeCoins speak is the familiar term "Expense".

Here's the main screen after recording the advertising expense.

The amount of cash has decreased $1000. Nothing surprising here. We didn't really need double entry accounting to see this. We've only had 2 transactions.

That afternoon, FastTrack Inc has seen our website and gives you $500 of work, which you do the same day. The customer comes over to say hello and check you out. He's fine with the work, which he picks up. He leaves a check, which you deposit in the bank the same day.

For this you record Income (FreeCoins speak for credit) in the revenue:fees_earned account, recording their check number. The matching account is your cash.check account, which gets debited.

Here's the main screen after recording the revenue.

Note that since you earned money, the matching principle of double entry accounting increased the blackness of both accounts by $500. The revenue account was raised from $0 to $500. The cash account, was raised from $4000 to $4500.

Now wait a minute. Did I say that? When I was putting money into the bank to start off the business, I said the same thing: I credited one account and debited another. That time instead of both going more "in the black", one account went red and the other went black.

What's happening?

This is why there are different types of accounts. Some accounts become more black when they are debited (e.g. cash, liabilities) and some become more red (e.g. expenses, revenue). This is what double entry accounting has over single entry accounting. In single entry accounting you are only concerned with whether you have more money or less (black and red). With double entry accounting you are concerned whether an entry is a debit or a credit. The system handles the black or red part without any intervention on your part. (This is why accounting is smarter than calculus).

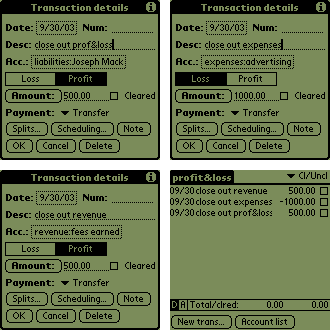

Lets fast forward to the end of the accounting period (say to 30 September) and lets say you do no more business till then. At that time you determine the profit and loss. For this you fold the revenue and expense accounts into a profit and loss account. This process is known as closing out the accounts.

An accountant can look at the balance in an account and will know whether a credit or debit is needed to close out the account. I don't know these things. Instead since the number of transactions in the accounts are small (here 1), you can enter a debit or credit for the value of the balance which zeroes out the account.

Here's the profit and loss account after closing out revenue and expenses.

Profit and loss has a balance that is $500 in the red. This is no big deal, you already knew you'd made a $500 loss. A loss here is not problem in the beginning as long as you have enough capital to pay the financial obligations as they come due (e.g. Amazon.com).

Here's the mainscreen after closing out the revenue and expense accounts (the balances in expenses and in revenue are all $0). Profit and loss has a liability (red) of $500.

The owner of a business doesn't get a salary. The owner gets money through an increase in his equity. When the equity has increased sufficiently he can withdraw some of it for his own use. The owner also cops any loss. So profit and loss are fine and dandy, but what the owner is really interested in is his equity.

Let's see if we can calculate the owner's equity at the end of the accounting period without using double entry accounting. You've put in $5000 initially. On top of that you made a loss of $500 (revenue $500 - expenses $1000). Using single entry accounting you ask the question "how much are you in the hole now?" (stop for a second here to get an answer).

To get the new owner's equity you keep some (or all) of the profit within the company to help finance activities for the next accounting period. You close out the rest into the owner's equity. In this case a loss was made and the owner gets the whole loss.

Here's the profit and loss account after closing it out into the owner's equity.

Here's the mainscreen after closing out the profit and loss account into the owner's equity.

The amount of cash in the bank is reasonable. The business started with $5000 and lost $500, leaving $4500.

Why isn't the owner's involvement in the business now $5500? After all it was initially $5000 and the business then lost a further $500. The owner is going to have to work harder to recover the extra $500. When I was setting this up, I made lots of mistakes. Is this another of my mistakes? (pause to think here).

The problem turns out to be that the question "how much am I in the hole?" is badly posed. Here are the questions accountants can answer.

$4500.

The business had an obligation of $5000 and lost $500. It only has $4500 to give back to the owner. This is the same question as "how much is the business worth or how much would the owner recover today, if the receivers came in and liquidated it?" (You can't get blood out of a stone, the business only has $4500 in assets.) If instead, the business looses the whole $5000, there's nothing the owner can recover.

This is the only question about the the owner's equity that's of interest to an accountant looking at the business's books. The business is only interested in what it owes the owner and that's all that is of interest to an accountant.

$5000.

He has a cancelled check from the bank proving it.

$5500.

This is the answer I expected when I asked "how much are you in the hole now?". This amount may be of interest to the owner, but it doesn't show up in the business's accounts.

The problem is that there are two different "you"s in that statement. The first "you" is the owner and the other "you" is the business. The mix-up comes about because the owner identifies with his business. The owner invested $5000 and the business lost $500. The two transactions affect the owner's equity in opposite directions.

As a technical person I always find it amazing or amusing that people can happily sit in front of a TV without knowing or even wanting to know how it works. I'm quite proud of my technical knowledge.

After finding that the answer in the previous section was $4500 rather than $5500, I realised that in the accounting world I was in the same position as the people who sit infront of a TV set and think there's a little band playing inside it.